Our History

Introduction

The history of our region and that of Ethekwini in particular is full of colourful characters, interesting facts and rich cultures. Pieced together these form the tapestry of our past, exposing both the blemishes and greatness of our humanity. This web page puts together some snippets of our history in the hope that readers will gain a greater awareness of our shared past while at the same time hopefully encouraging them to explore the subjects in greater detail.

The Durban System

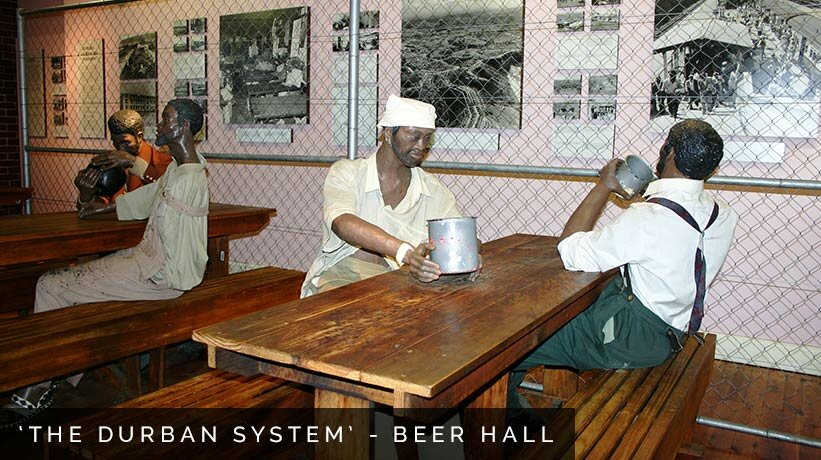

In the early years of the twentieth century Durban’s population level was relatively low. In 1900 the total population of the town was about 55700 of whom 14600 were African. By 1921 the total had risen to 90500 most of whom were male. This increase prompted the establishment of a structure to administer Africans. This structure of control was built on the revenue derived from the municipal beer monopoly and became known as the “Durban System” with its roots embeded in Theophelus Shepstone togt labour system.

Read More

The authorities in Durban were keen to have black people in town for their labour but they were concerned that the relatively small white community would be overwhelmed if uncontrolled black urbanization was allowed. The Durban System responded to this concern and sought to control the influx of black people by requiring them to have permits authorizing their presence in town while accommodating them in single sex hostels and townships. The Durban System would have cost rate payers a lot of money but the authorities made it self-financing. In terms of the Native Beer Act of 1908 municipalities in Natal were given the sole right to brew and sell beer within their boundaries.

The Durban municipality brewed its own beer and sold it through its network of beerhalls. The first municipal beerhall opened in 1909 and the system soon reaped huge profits. Nothing was to be allowed to threaten this situation and every effort was made to stamp out the illegal brewing and sale of beer through regular police raids. Durban remained the only town in South Africa with a self-supporting Native Revenue Account between 1909-1930. Revenue from the beer monopoly was ploughed into the maintenance and establishment of barracks, beer halls, hostels and breweries, and subsidized the cost of policing the town. Great numbers of people lost the means to earn their living through this policy and even if they did not stop brewing beer, there was always the risk of a raid. The beer in beer halls was expensive and this led to great bitterness and outbreaks of violence, including one in 1929 in which a number of people were killed.

(The Durban System exhibition at the Kwa Muhle Museum provides more information detail on this subject.)

Suburbs and Townships

Lamontville Township : ``The Roots of African Townships``

Lamontville was established in 1934 and named after Rev Lamont, Mayor of Durban from 1929 to 1932. It is the oldest African township in Durban and was intended to contain and co-opt the African middle class.

Initially the authorities objected to the creation of townships for African people in urban areas as this encouraged permanence. On the other hand, the liberal organisations like the Joint Council for Europeans and Natives pressured the Durban Local Authorities to establish a village for Africans.

In 1931 The Durban City Council acquired Woods Estate (later renamed Mobeni) for industrial purposes setting aside 425 acres of land which were unsuitable for industry for the establishment of Lamontville Township. This development occurred in four phases, in 1932-34 the old location, 1937-39 ‘new look’ cottages, 1948-53 flatted houses and flats, 1955-61 houses in letting-selling schemes of Gijima , Nylon and Ezigwilini.

Lamontville Protests : ``Asinamali``

After the building of Lamontville many dilemmas were faced by the community. Different grievances were expressed to the authorities including, insufficient maintenance, improvement of the social wage and the problem of expensive transport. Tensions between Africans and the established Indians bus operators grew with huge hostility developing after two African bus operator applications were turned down. Though not the cause, the continued tension manifested itself in 1949 riots. Indian buses became a target of the attack and many were damaged. The agitation against Indian transport enabled the city council to expand their transport operations to Lamontville.

During the late 1940’s, 2800 authorized people resided at Lamontville, yet only one private bus owner operated a bus to the township. In 1953, the Durban Transport Management Board (DTMB) was established and planned to expand services to African townships. In 1955 the DTMB obtained a certificate to operate to Lamontville and other areas and its first operation began in 1957. Immediately after DTMB began its operations, the fares were increase by 3d. In 1959 unrest in Durban resulted in serious financial losses to the DTMB’s transport with nine municipal buses being destroyed. The unrest spread to Lamontville, Cato Manor and Umlazi.

By 1982 The Port Natal Administration Board announced an increase of rents by 63 percent. The Lamontville community was also discontent about the lack of proper local consultation, and accused the board for failing to adequately maintain the township. In 1983 Lamontville became the scene of serious urban violence. The rejection of rent hikes led to a the slogan “Asinamali” (we have no money) in response to the exorbitant transport and rent increase. A bus boycott was planned for one day on the 1 December 1982 but it lasted for months in Lamontville. The township communities mobilized against the increases and this led to the formation of Joint Rent Action Committee (JORAC). Harrison Msizi Dube was one of the leaders of JORAC, because of his articulate manner in describing the problems faced and his portrayal of the failure of the Local Council to curb the rent hikes, he became unpopular within the council. On the 25 April 1983, Dube was murdered and violence broke out in Lamontville. The other aspect which perpetuated violence was the governments announcement of the incorporation of Lamontville into KwaZulu. JORAC and the majority of residents were opposed to the move fearing the loss of Section 10 rights. JORAC affiliated to United Democratic Front (UDF) and Inkatha clashed as JORAC and the youth opposed the incorporation. Tension and clashes continued through the 1980s and early 1990s.

RISING FROM THE ASHES

Lamontville, which was established as Durban’s model village became the space of resistance and struggle for liberation, where people attempted to resolve and change the conditions experienced on a daily basis. Even when political instability was at its height the people of Lamontville did not stop excelling in different activities such as politics, sport, art, and culture.

The development of the Port of Durban

THE BAY AND EARLY HISTORY

Prior to the development of city, the Bay of Natal was a large estuary which stretched from Virginia in the north to Isipingo in the south. Fed by several rivers, the bay included islands, like Salisbury. The ocean side was fringed by the Bluff and the Point forming a shallow entrance channel which dominated the making of a safe harbour for many decades. The edges of the Bay were densely wooded, in places with mangroves. As early as 1687 shipwreck survivors built the Centuar from the wrecks and from milkwood trees. The centre of the docks was established at the Point in 1838 at the stone Customs House of the Republic of Natalia on the beach. This was incorporated in the first British fortifications and later Customs Houses remained at the centre of the port activities. The Bay offered many other opportunities for fishing and recreations like boating and yachting.

TWO PIERS AND A CHANNEL

Safe entry for ships into the Bay was blocked by a shifting sandbar which lay in the shallow entrance channel. For over sixty years this challenged many eminent engineers. At first John Milne devised a two pier solution to confine the ebb tide and move the sand. After he was dismissed an abortive scheme was begun by Vetch and Abernethy, but achieved little. In 1881 Innes under the powerful control of Harry Escombe, the chairman of the 3rd Harbour Board, continued Milne’s North Pier and started a South Breakwater. After his death Cathcart Methven carried on the two piers with a training wall. A huge public and political controversy erupted over their relative lengths. Large fifty ton concrete blocks were produced in two blockyards. Then dredging with powerful dredgers took over and by 1904 ships could safely enter through a deeper channel.

QUAYS AND DREDGING

Early timber jetties and wharfs gave way to stone and concrete quays by the 1880’s. These were built within staging and timber piles at a distance from the shore. Pile drivers hammered the piles deep into the floor of the Bay. The dredged spoil was then pumped into the intervening space to form a new quay. Divers grouted the blocks and ensured the walls were vertical. By the end of the 19c the port had the largest fleet of dredgers in the world dredging out huge quantities of sand from the sand bar, the entrance channel and the inner harbour. Dredgers like the Teredo – a bucket dredger, and pump dredgers Octopus and Walrus played a major role in forming the port. Combined with tidal scour, dredging effectively removed the problem sandbar and created a larger and safer entrance channel.

SHIPS: FROM SAIL TO STEAM

During the development of the port, the driving power for ships changed from sail to steam. Initially small vessels, many of them coasters, plied between the port and Cape Town and Mauritius. Larger barques, brigantines and schooners ventured further to Britain. Europe and the East. In the 1850’s many immigrant ships arrived but waited at the outer anchorage to discharge their passengers and cargo. Tugs provided useful towing services, so from the 1870’s sailing ships crowded the limited berths, often three abreast. In the 1880’s steamers, often with sails aloft, berthed directly at the extended wharfs, and by the early 20c larger cargo ships and liners could safely enter the port guided by pilots and tugs. On 26 June 1904 the 12 967 ton Armadale Castle entered the port.

SHIPWRECKS

As long as sailing ships were forced to remain in the open roadstead they ran the risk of being wrecked. While there were two wrecks on the Bluff rocks including the famous Minerva in 1850, about forty took place on the beach between the North Pier and the foot of West Street. Among the causes were strong ocean swells; inadequate anchors and chains and empty ships bobbing up and down in the waves. Another probable cause was that anchors were swallowed up in the loose sandy floor of the roadstead. One, the Onaway, resulted from faulty navigation when she came in on the wrong side of the South Breakwater. Courts of enquiry were held after most mishaps with the purpose of establishing whether the master, or captain of the ship, had been at fault. One wreck of the 20c was the Ovington Court off Addington Beach on 25 November 1942.

PASSENGERS

As most ships were forced to remain at the outer anchorage for long periods before enteringthe harbour, passengers were transported in small vessels like surf boats which could cross the sandbar. On arrival on the beach at Point they found no facilities. Later passengers were lowered by basket from ships onto tugs and lighters. Indentured Indian workers were also brought ashore in this manner but then spent weeks at the Quarantine Station on the Bluff shore. Later in the 19c facilities were built for arrival and departure in the form of a landing jetty together with a T Room and baggage shed. Even after ships could enter safely they were moored in channels in the Bay and passengers still had to travel in open boats. By the end of the 19c ships moored at the quayside allowed passengers to board directly via gangways. By this time there were refreshment kiosks on the quays.

CARGO

Among the earliest goods exported through the port were cattle, hides, skins and ivory. Many basic foodstuffs and domestic articles came from Britain and its colonies. For most of the 19c there were far more goods imported than exported. It was common to see sailers riding high in the Bay awaiting export cargoes. Handling cargo across ships berthed side by side was a nightmare, and so was the serious congestion and ‘blockages’ caused by inadequate space at the Point wharfs. By the 1880’s most cargo handled manually by stevedores or cranes was destined for the interior republics and the port assumed a major transhipment role. At this time bulk goods like maize and sugar were moved in sacks directly from or into rail trucks. Vast amounts of timber were imported for the mines in the hinterland and special timber jetties were provided.

CRANES

Equipment in the port changed from earlier hand driven devices to ones using steam, hydraulics or electricity. This was also true of cranes – an essential component of cargo handling. Hand winches and steam grabs were the earliest. A mobile railway crane needed its own steam equipment and became a fire risk. Steam also powered the sheer legs – a tripod type structure with one leg firmly anchored in the quay. By the 1880’s five ton cranes along the wharves were driven by water power produced, together with electricity, in the hydraulic station. One 50 ton crane could even lift small launches. The final stage in this evolution was the use of electricity.

WORKERS

The port needed many different types of work including: boating, construction of piers and quays and stevedoring. Thousands of monthly contract workers and togt labourers (daily workers) were used. They came not from Natal and Zululand but from Tongaland, Mozambique and regions along the east coast of Africa and India. Accommodation was primarily in several large controlled compounds which dominated the Point. This system of labour control formed an important element of what came to be called the “Durban System”. The harbour also required semi-skilled and skilled labour for a multitude of purposes. Convicts were used for rock breaking and road making. By the time of the Bambatha Uprising in 1906 many thousands involved in the uprising, some elderly, became available and were housed in the Point Convict Station.

TRANSPORT

A fundamental part of a functional port is transport – moving cargo and passengers to and from ships. Ox wagons dominated the port scene at the beginning and even when the first Durban to Point railway was built they still had the advantage of providing quay to door deliveries. The first railway of 1860 was too short to be financially viable and when it was absorbed into the Natal Government Railways it still could not compete with horse and mule drawn trollies. But these were only of local use and the expansion of the railway network around the port enabled vast quantities of goods to be transported to the hinterland and products to be exported. By the end of the 19c horse-drawn and electric trams together with rickshas provided transport for workers, passengers and the general public.

COAL BUNKERING

The advent of steamers brought the need for coal and methods of getting the fuel into the ship’s bunkers. Initially Welsh and English coal was shipped to the port on sailers, until the development of the Natal coal industry. The earliest bunkering was done by African men hauling sacks from rail trucks up ladders onto the ships. Coal was stored in ship’s hulks or railway trucks. By 1907 mechanical systems were introduced on the Bluff with a McMyler ‘side dump bucket car-dumping machine’ for pulling the 71 ton coal rail truck into a cradle. The coal was tipped in buckets into a massive storage bin or onto a cantilevered transporter from where it was dropped into the ship’s bunkers.

TUGS AND PILOTS

The port has always required certified pilots to safely guide ships in and out of the port and by 1859 had its first steam tug – the Pioneer. This was followed by the Forerunner with a shallow draft and paddle wheel. Both had very chequered careers. Then came a larger tug -the Churchill. There were also several private tugs operated by shipping companies like the Adonis and the Natal. They were usually moored at Lifeboat House Corner, ready to move quickly through the channel to give aid to a sailing ship in distress, or to tow a vessel to safety. Before pilot boats these were the vessels used by pilots to nudge ships towards their berths. They were also used extensively for shifting grounded vessels and, like the Union, for carrying passengers or as small coasters.

CHARTS AND SIGNALS

Navigational aids are indispensable in a port. Early charts like Nourse’s mapped the shifting sandbar. A private look-out on the Point and a signal station on the Bluff with a light in a window, gave information about ships and for ships. Leading marks aided entry through the channel, and semaphore flags gave coded signals. Later charts were more complete. The port was provided with a lighthouse in 1867. In the late 19c two signal stations, at the Point and on the Bluff co-ordinated the control of shipping. To provide accurate time a timeball was erected on a sand dune at the Point. This was regulated from the Natal Observatory in Currie Road, and triggered by a telegraph signal. Early in the 20c a higher crow’s nest was built on the roof of the Natal Harbour Department offices in Point Road for the Port Captain to view shipping both in the harbour and at the outer anchorage.

WHALING

In 1907, Norwegian Consul Jacob Egeland and fellow Norwegian, Johan Bryde formed the South African Whaling Co with two catcher vessels, Omen and Fell. Their first catch in 1908 totaled 106 whales. The whaling season was from March to September during the whale migration northwards at the start of the Antarctic winter. Most were caught within 250km of Durban and killed with explosive-headed harpoons, the gun mounted in the bow of the catcher, like the later WR Strang, and Oom Kappie. Their carcasses were then filled with compressed air and towed to Durban’s whale slipway where they were hauled out and cut up with flensing knives assisted by winches. The bad smell necessitated the station being sited on the seaward side of the Bluff, the whales hauled there on flatcars by steam loco from the slipway. In 1909 Egelund and his cousin Abraham Larsen started Premier Whaling & Fishing Co and in 1922 they founded Union Whaling Co. Lever Brothers sold out Premier to Union Whaling Co in 1931. The Union Whaling shore station was the largest in the world, but the company also conducted pelagic whaling operations with the factory ships, Uniwaleco (1937), and the Abraham Larsen (1949). Whale spotting by plane started in 1954 using a De Havilland Rapide, and later a red twin-engined Piper aircraft. Whaling operations off Durban ended in 1975.

MAYDON WHARF

Maydon Wharf was developed in response to the need for Durban Harbour to exp and, particularly to the requirements of the developing Witwatersrand. The early berths were built of timber and progressively extended. Berths 1-4 and 13-14 were rebuilt with steel sheet piling during the 1950s. The Grain Elevator at Berth 8 was built in the 1920s while the Lever Bros factory stood opposite Berths 3 & 4. Illovo Sugar’s early warehouse was opposite Berth 6. From 1922 the Pure Cane Molasses Company used Berth 7, moving to Berth 9 in 1962. By 1937 Maydon Wharf had reached the existing Berth 15 although Berth 11 was only built in 1950 as a dolphin berth. During the 1960’s Berths 5-7 and 9-10 were rebuilt in concrete. Berths 10, 11 and 12 are today part of a multi-purpose terminal. In 1965 the first ship was loaded from the new Sugar Terminal at Berth 2. In 2005 a Woodchip Terminal was built next to the Grain Terminal and shares the loading gallery. A specialist fruit terminal was opened in 2004 opposite berth 7. Berths 13 and 15 are today used mainly for forest products but Berth 15, originally a landing wharf for the Graving Dock, was once the Manganese wharf, while berth 14 today caters for the import of soda ash.

PRINCE EDWARD GRAVING DOCK

The advent of vessels of more than 18 000 tons caused a decision to be taken before WW I to construct a graving dock, for which detailed post-war borings revealed ideal bedrock at Congella. It was one of the three largest docks in the world in length and depth and was constructed departmentally, ‘in the dry’, under Resident Engineer, W R Crabtree. Excavation by a large manual labour force, assisted by Wilson steam excavators commenced in March 1920. The spoil was removed by rail wagons and locomotives. The excavated entrance basin was separated from the bay waters by a berm wall and kept dry by pumps. The dock can be filled in under 50 minutes, whilst its three pumps empty the dock in four hours. The dock was officially opened in 1925, and has since accommodated large modern container ships such as the Helderberg. A 700ft (213m) quay wall was also constructed on the north side of the entrance basin for ships destined for the dock and is now known as Berth 15, Maydon Wharf.

OIL AND CHEMICAL STORAGE ISLAND VIEW & FYNNLAND

After WWI the increasing number of oil-fired ships necessitated the development of oil tank farms with berths. In 1919/20 dredging started on the Island View Channel, the first oil tanks being erected in 1921 in the Sand Quarry sites. The first timber wharf (later Berth 5) was complete by 1925. Reclamation proceeded and the wharf extended in 1940 with concrete caissons (ex T Jetty). By 1943/4 wharfage was further extended westwards by steel sheet piling and eastwards with the construction of Dolphin Berths 2 to 4 and Berth 1. Reclamation behind was complete by 1954, and the timber wharf was replaced by steel sheet piling. By 1963 Berths 7 & 8 were complete with Island View Turning widened and deepened together with the reclamation of 330 acres (Fynnland Sites) west of the Salisbury Island Causeway. These were mainly for the large strategic crude oil tank farms, but also for Petro-Chemical tank farms. Berth 9 on northern shore of Island View Turning Basin off Salisbury Island was constructed in 1969, initially for crude discharges, but later exclusively for jet fuel. The only non-petro-chemical terminal at Island View is the large Silo Complex of Durban Bulk Shipping for various granular products.

POINT DEVELOPMENT POST 1910

By 1910, the Point comprised over 3000m of quay wall, nine cargo sheds and over forty hydraulic cranes, including the 50t Heavy Lift crane, superseded in 1933 by the 80t crane at C Berth. By 1924 there was the Cato Creek Goods Shed with four sub-divisions to serve the four provinces. Rail yards were also established and in 1935 the Esplanade Railway linked the Point with the Congella Rail Yards. The quay wall for Q & R berths was completed by 1940. The T Jetty quay wall, of concrete caisson construction, was built around the Floating Dock at the Point, itself used for caisson casting and launching. By 1943, her work complete, the floating dock sides were dismantled and her hull was towed out through the final two-caisson gap. T Jetty was completed after WWII during which O Shed saw SA troops departing and Italian POW’s arriving. 1910-1950 was the heyday of passenger liners like the Empress of Britain . B Shed became the Mail Boat berth until the completion in 1962, of the new Ocean Terminal at M Berth, T Jetty.

FLYING BOATS

For two decades from 1937 Durban Bay was in regular use by flying boats. First were the graceful Short C flying boats of Imperial Airways which inaugurated a passenger service between England and South Africa with the Bay as the southern terminus. Salisbury Island acted as the ‘airport’ until a base was provided at the Bayhead. In 1942 following an increase in German U-boat activity off the SA east coast, a squadron of Consolidated PBY Catalina flying boats of RAF 262 Squadron operated coastal reconnaissance and anti-submarine patrols off the Natal coast and southern Mozambique Channel. This squadron later became 35 Squadron of the South African Air Force. In 1945, 35 Squadron was re-equipped with four-engine Short Sunderland flying boats which remained the backbone of coastal reconnaissance until the advent of the landbased Avro Shackletons in 1957.

THE LEGENDARY STEAM TUGS

The great tugs built before 1910 but still serving the Port of Durban at the time of Union were: • Richard King (1891-1939) • Sir John Robinson (1897-1936) • Panther (1899-1933) bought from African Boating Co in 1910 • Harry Escombe (1902-1953).

After 1910:

• Sir David Hunter (1915), in Durban from 1915 , sank at the end of Esplanade Channel in 1941, salvaged and served till 1960. • Sir William Hoy (1928), in Durban 1928-1979. • John Dock (1934) only served in Durban for her last few years before being scrapped in 1977. • T Eriksen (1936), in Durban 1936-1965, sank off Maydon Wharf Berth 14 with the loss of three crewmen, then salvaged and refitted , served in Port Elizabeth till 1977. • Otto Siedle (1938) , in Durban 1938-1980, was credited with fourteen acts of mercy, and used as a torpedo target by SA Navy in 1981. • JD White (1950), the last of the coal-fired tugs, served most of her years in Durban, then in Port Elizabeth till 1980. • Both the magnificent AM Campbell (1951), first of the oil-fired tugs and the FC Sturrock (1959) served most of their years in Durban before working in Walvis Bay, scrapped in 1982 and 1984 respectively. • The three steam pilot tugs, Ulundi (1927), a permanent exhibit at this Museum, the Harry Cheadle (1945) and the JE Eaglesham (1959) also did sterling service in the Port. • JR More (1961), the last of this proud line of steam tugs, designed for both ocean salvage and harbour work. She served in Durban till 1984 and is also on permanent display as a floating exhibit at this Museum.

PIERS 1 AND 2 CONTAINER TERMINAL

The general shallow draft of the old Point berths and the growing need for deep water general cargo berths gave rise to the construction of Pier 1 off Salisbury Island. This had a draft of 12,8m, and four Cargo Sheds, serviced by rail yards and a Harbour Craft Quay. This was begun in 1965 and was immediately followed by the Crossberths 108 & 109 for RORO cargoes and then in 1970, by Pier 2 for a Container Terminal. The substructure of all these quays was identical, consisting of 120 ton concrete blocks, five courses high, laid on a prepared stone bed. The gaps between blocks were filled with stone. On this wall a reinforced concrete mass cap, complete with service tunnels, bollards, etc, was cast. As the surrounding sandbanks were dredged away to create the basins, the sand was pumped in behind the walls and also to the south-west to create land for Kings Rest Rail Marshalling Yard. The final block for Pier 2 was laid on 1st March 1974. In time Pier 1 would be converted to a Multi-product Combi Terminal and, in 2005, to a fully-fledged Container Terminal whilst Pier 2 would be re-equipped and upgraded.

NAVIGATIONAL AIDS AND SHIP TRAFFIC CONTROL

The iconic Millenium Tower at the eastern end of the Bluff, built in 1999, replaced the old Bluff Signal Station. Constructed during the 1950’s, it had replaced the original two-storey high Signal Station. The Port Captain’s personnel who man the Millenium tower, with towering aluminium cowl and yellow tail indicating wind direction and tall spire and moving orange marker indicating tide level, control all ship traffic movements into and out of the port, and in the port, from the moment the vessel is picked up by radar or makes radio contact on its approach to Durban. The Port limit is four nautical miles off the entrance. Permission to negotiate the Entrance Channel is indicated by two large banks of green and red lights on the tower, coupled with radio command. Prior to the widened entrance channel, Harbour Pilots kept ships in the centre of the channel by keeping the Front and Back Leading Light towers with their lights and day marks aligned, as they ran in on the projected transit line. The new channel centre line moved northwards, but was masked by the tall Durban Bulk Shipping Silos, leaving less separation between front and back marks. A new PEL Sector Light system is now in use. All channel marker buoys and lights within the port comply with the International Association of Lighthouse Authorities (IALA) Region A, which means that, proceeding into the port, all starboard channel buoys and lights are green, and those on the port side, red. In earlier days, the pilots were taken out to incoming ships by steam-driven pilot tugs and later by diesel-driven launches like the Roy Forbes, but are now flown out an Agusta A109 K2 ‘HPS’ twin-engine 8-seat helicopter, operated by Balmoral Maintenance Services.

NEW BERTHS D-G AT THE POINT

By 1990 the old shallow draft, general cargo, Point Berths D, E, F & G, were already no longer commercially viable. The decision was taken to build a new deeper draft quay D-G at a cost of R355 million, and relocate Pier 1 Combi Terminal operation to City Terminals and convert Pier 1 for container operations. Caisson construction was chosen. Starting in Feb 2002, 52 concrete caissons of 3 000 tons mass were constructed at Bayhead, moved to the launch cradle on 8 x 500 ton trolley jacks, lowered into the water by 8 x 500 ton strand jacks and towed by tug to site. They were then sunk in sequence onto a prepared stone bed and filled with sand by Transnet dredger, Piper. A concrete mass cap with bollards completed the quay wall. Some 3 million cubic metres of sand was dredged at sea and pumped in behind the new quay wall by the Belgian dredger Filippo Brunelleschi, creating a cargo stacking area of some 20ha. Fill compaction by impact roller followed by 350mm thick concrete paving (to carry five high loaded containers), high-mast lighting and other services completed the project. The dramatic increase in the high value car terminal trade has dominated this new facility.

WIDENING THE ENTRANCE CHANNEL

A major feat of engineering and team work, this was carried out from 2005 to 2010 at a cost of R2,9 billion and had to be undertaken without affecting the normal passage of vessels of all sizes into and out of the Port. A new deep service tunnel had to be bored (using a TBM Tunnel Boring Machine) under the entrance channel with vertical entrance shafts each end. Once completed Durban’s CBD main sewer trunk mains, electric cables, etc were rerouted from the old through the new tunnel. The old tunnel was then demolished, cut into smaller portions by divers using diamond wire saws and removed. Most tunnel portions floated and were towed out to sea and sunk while others needed to be lifted out by crane and broken-up. The new North Groyne was constructed using material from the old North Pier demolition, before excavation and dredging for the channel widening and deepening could take place. The suction dredger Mariske, and the world’s largest Grab dredger Pinocchio were deployed for this work. The South Breakwater was also strengthened and re-armoured with 40t antifer blocks.

SOURCE: PORT NATAL – PORT OF DURBAN, exhibition at the Port Natal Maritime Museum, September 2012.