The oral history of political violence as an education tool at Mpumalanga Township

by STEVEN KOTZE

Oral history serves a vital role in the context of local museums in South Africa. Not only as a means of recording the memories of survivors and participants in a central event of apartheid-era violence, but also to serve as an educational tool for a younger generation of South Africans.

The impact of a recent oral history project in eThekwini Municipality’s Mpumalanga community has been to raise the profile of the aged people who experienced this violence and survived.

Young members of the community now also have a clearer idea of the events that took place more than 20 years ago. It is of vital importance that experiences of the violence are related by survivors, and not by static museum display texts.

Along with the rest of South Africa, political tensions rose within all sections of Mpumalanga township during the late 1970s and early 1980s, during the final decades of apartheid. From August 1985 a wave of widespread and deadly political violence consumed the township for the next seven years. During that time Zulu nationalists belonging to the Inkatha organisation and linked to the government, engaged in war with members of the progressive United Democratic Front (UDF), which was then effectively a proxy of the banned African National Congress (ANC). Members of other progressive organisations such as Azapo were also targeted by Inkatha and the security forces that colluded with Inkatha.

The new Mpumalanga Heritage Centre, which was completed in July 2014, and where the oral history of apartheid-era political violence will be used in exhibition displays.

The newly completed Mpumalanga Heritage Centre will complement seven existing sites of the Local History Museum and will serve a range of functions. These include a site of memory for the community of Mpumalanga, an educational resource, and an orientation centre for visitors. A process of ongoing consultation with the community and stakeholders, managed by the Local History Museum, has determined which aspects of the broad history should form focal points for content in the heritage centre. The Mpumalanga Heritage Centre has a responsibility to reflect two complex narratives; political violence from 1983 to 1992, as well as the 20 years of peace and democratic government that have passed since the end of violent confrontation, in a manner that promotes social cohesion within the community that suffered this conflict.

Central to this process is the documentation and preservation of oral history concerning events at the end of apartheid in Durban, specifically at Mpumalanga township. The following article demonstrates the importance of oral history in local museums’ context of South Africa. Three important issues have emerged from the Local History Museum research conducted at the site: 1) Oral history is a vital means of recording the memories of survivors and participants in a central event of violence in apartheid history. 2) Oral history serves as a corrective source of information to published sources containing certain inaccurate details. 3) Oral history also serves as an important educational tool for a younger generation of South Africans, who are able to hear historical accounts from the perspective of those who witnessed the events.

Introduction

Professor William Beinart has pointed out that violence was a normalised feature of life during apartheid in South Africa (Journal of Southern African Studies, 1992). For several years though, from 1987 to 1991, the KwaZulu-Natal township of Mpumalanga saw political divisions based on disputed views of Zulu social structure transformed into brutal and socially devastating forms of violence. In the period of transition at the end of apartheid under National Party rule to the establishment of democracy, this particular settlement was subject to harrowing killings of unprecedented intensity committed largely by young male political groups within the Inkatha on one hand and UDF/ANC on the other (Bonnin, 2007).

After attacks and reprisals reached a peak in the first half of 1990, a process to negotiate peace between the warring factions was cautiously engaged towards the end of that year. Over a period of two years leaders from within the community first established a truce and finally concluded an agreement that brought an end to open hostilities. The Mpumalanga Peace and Development Trust was created as part of that peace agreement (Innes, 1992; Boulding, 2000). The Trust has been instrumental in its motivation to build a heritage centre that commemorates those who died during the violence, and document the events of that era for the sake of posterity and for the youth of today.

Through consultations, the community and stakeholders have determined what aspects of the broad history should form focal points for the content at Mpumalanga Heritage Centre. The overview that follows below consists of topics that emerged from secondary reading on the political violence, which serves as context for the oral history recorded during interviews conducted with members of the community.

Background to Mpumalanga (1862-1968)

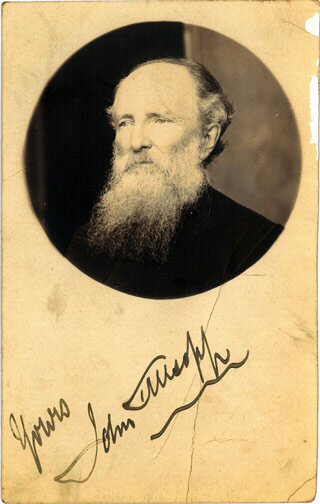

Methodist missionary Rev. John Allsopp, who founded “Peaceville” in 1862. The mission later became the township of Mpumalanga

The township of Mpumalanga is situated on the former Methodist mission station ‘Peaceville’ established by Rev. John Allsopp on the farms Woody Glen and Georgedale in 1862 (Faith Marches On, 1956). Allsopp created a community of landowning African Christian converts (known as amakholwa or ‘believers’), who bought property from the missionaries. Land and ownership were central to the original settlement of Mpumalanga.

In 1913 the Natives Land Act restricted all new purchases of land by Africans to existing reserves, which were limited to only 50% of the arable land in South Africa for 85% of the population. Most reserves only allowed communal tenure and very few reserves permitted individual tenure for Africans to buy land in their personal capacity (Beinart, 2013; Etherington, 2005). As a mission reserve ‘Peaceville’ allowed Africans to become landowners, which made it attractive to amakholwa who purchased property there in their own right (Laredo, 1968).

Combined with the particular legal status which permitted Africans to buy, own and lease land, the Methodist mission farm was also close to Durban and Pietermaritzburg, and near to the main transport route between these two towns. The kholwa mission ‘Peaceville’ enabled a different set of living conditions to emerge among residents there. The Christian owners were not governed by the Natal Code, and women could own land too, while the local chief was elected by the community without holding hereditary office, as was customary in rural Tribal Reserves (Laredo, 1968; Marks, 1989).

These conditions attracted a growing community at ‘Peaceville’ mission during the middle of the 20th century. By the 1950s the community on Georgedale farm was divided into three groups, namely the original kholwa settlers who had been landowners since the mission was established, more recent arrivals who had also bought land in the mission and finally, their tenants. In order to coordinate the increasingly difficult question of land purchase, transfer and inheritance, in 1948 Georgedale residents formed the Bantu Land Owners’ Union (Laredo, 1968).

In some ways the terrible violence that erupted at Mpumalanga 30 years later can be traced back to disagreements over land management that arose in the mid-1950s. Other political changes, however, were the result of economic developments. Industrial expansion began in 1958 when clothing manufacturers moved their factories from Durban and Johannesburg to Hammarsdale. Trade union activity was introduced to the community for the first time in the form of South African Congress of Trade Unions (SACTU) (Bonnin et al, 1996).

‘Peaceville’ mission and the neighbouring industries of Hammarsdale were then identified by apartheid planners as a so-called ‘decentralisation point’, to draw African workers away from cities in an attempt to reverse the process of urbanisation. Land was simply expropriated from owners or tenants of small properties, with the promise of a house in the new township. A plan for the construction of 10 400 houses was completed at the end of 1966, and Mpumalanga township was formally created in 1968. According to Debby Bonnin, ‘The creation of the township and the new political structures that were put into place ultimately provided the basis for the support which Inkatha was to generate and then fight to maintain in the 1980s’ (Bonnin, 2007).

Youth, elders and political opposition (1968-1985)

After a decade during which resistance was forcefully suppressed by the Nationalist regime and ANC leadership was imprisoned or exiled, during the 1970s another generation of activists rose to confront apartheid. In Durban workers embarked on the 1973 strikes in order to achieve a living wage, and three years later young learners around the country took part in an uprising against the discriminatory basis of Bantu Education (Brown, 2010).

A different political approach was also initiated in 1975 when Chief Mangosuthu Buthelezi founded the Inkatha National Cultural Liberation Movement, known as Inkatha (Maré and Hamilton, 1987). Due to Buthelezi’s former position within the ANC Youth League, Inkatha was initially seen as an element of the progressive liberation movement. During the late 1970s however, it became apparent that Inkatha’s ideological stance was based on a narrow and exclusive version of Zulu identity, which strongly emphasised patriarchy and notions of customary respect (known as ukuhlonipha in Zulu).

When Inkatha was launched as a new political party in 1975 a branch was established at Mpumalanga (Mlaba interview, 2014). Leadership within this branch appealed to more traditional elements within the landowning elite of the former mission, and made efforts to bring the township under the broad control of Inkatha. In response the Mpumalanga Resident’s Association (MPURA) was formed partly to challenge the idea that there was an overarching Zulu identity that all Zulu-speaking Africans subscribed to (Maylam, 1991). The Resident’s Association also represented the long established tradition of land owners of Georgedale and Woody Glen, who sought self determination and the right to elect leadership, in opposition to hereditary tribal leadership.

At the start of the 1980s, like much of the country Mpumalanga township was made up of a wide variety of diverse political and community organisations. Associations such as MPURA and trade unions operated alongside church groups and choirs, while outlets for political expression were found in authorised organisations such as Inkatha and the Black Consciousness movement Azapo.

Meanwhile a variety of informal criminal organisations formed by young male gangs operated in commuter bus ranks and along footpaths, known by names such as Mapantsula’s, the American Dudes and other appellations (Khumalo, 2006). In response to increases in the criminal activity thriving at that time, groups of older men formed themselves into vigilante enforcers who were known as oQonda (meaning ‘to straighten up’) (Von Kotze, 1988). For many older residents the move from mission land at Georgedale, with its structure and ordered living, had been replaced with a widespread lack of respect (hlonipha) in Mpumalanga.

In contrast with the older, patriarchal and tribal sense of ‘Zuluness’ advocated by oQonda, young and politically aware men in Mpumalanga were drawn to the principles of radical Black Consciousness they found in the Azanian People’s Organisation (Azapo). First founded in April 1978, but re-launched in late 1979 when its leadership was released from detention, Azapo offered a subtle and sophisticated analysis of the South African situation (Mkhabela, 1986).

Essentially, Azapo saw the struggle against oppression in terms of class, and their policies identified the vital point that certain Africans would collaborate with apartheid authorities if it served their class interests to do so (Lodge, 1983). This resonated among certain sections of the Mpumalanga community, particularly the youth from families excluded from the former land-owning elite of Georgedale and ‘Peaceville’ mission (Khumalo, 2006).

A branch of Azapo was launched at Mpumalanga in late 1982. The membership of this branch proved to be a particularly important source of new political ideas and class theory among the youth of the township. A year later the United Democratic Front (UDF) was officially launched in August 1983, although it had been operating in Natal since May of that year (Seekings, 2000). The UDF adopted the Freedom Charter, a statement of the aims for a free South Africa and basis for a democratic constitution, which it shared as a basis of policy with the ANC.

The increase in political activity in the early 1980s did not benefit Inkatha, which saw support eroding among older people who had voted for MPURA in recent township council elections; now the youth began participating in Azapo and UDF structures, which caused further losses to their membership (Khumalo, 2006; Bonnin, 2007). These circumstances led directly to the outbreak of terrible politically motivated violence in 1985.

Conflict and the outbreak of violence (1985-1991)

The incessant and devastating personal attacks and arson, which lasted over five years in Mpumalanga, form the centre of the oral history project co-ordinated by eThekwini Municipality’s Local History Museum. Interviews were arranged as part of the process to create the new Mpumalanga Heritage Centre, with participation of all major parties involved except for former representatives of the South African Police (SAP) and South African Defence Force (SADF) who declined the invitation. By recording the testimony of participants and survivors of this late-stage apartheid violence the museum has provided certain unique insights to those events, as well as subsequent histories that have been written.

Tensions rose within all sections of Mpumalanga township during the course of 1984 and 1985, both as a result of general opposition to apartheid and the particular history of conflict over land that existed at Mpumalanga. On 5 August 1985 the Durban-based lawyer Victoria Mxenge was assassinated at her home in Umlazi, and youth across the province of Natal took to the streets in protest (Minnaar, 1992; Bell, 2003). After looting, robbery and arson followed in the wake of these protests, Inkatha leaders at Mpumalanga mobilised militia groups known as amabutho to protect their property and businesses. Road blocks were erected around the township and Azapo leaders from outside the area were detained for questioning by these unauthorised militia (Bonnin, 2007).

Within days the situation escalated and homes of prominent Azapo members were attacked by unidentified persons using petrol bombs. Although many young members of Azapo were determined to avenge these assaults on their fellow members, older comrades prevailed with a calming influence. After much debate it was decided that Azapo cadres would guard their response and only retaliate if their organisation suffered a death at the hands of Inkatha. An attempt at bringing peace to the community, with the formation of Black Unity Youth Association, was a short-lived initiative at this time (Bonnin, 2007).

Far more significant, towards the middle of 1986, was the formation of Hammarsdale Youth Congress, a group that became known as Hayco (Gumede interview, 2014). Largely made up of young men who were formerly members of Azapo, this militant organisation was determined to defend the youth from attacks by Inkatha. The creation of Hayco was essentially a catalyst for the violence that broke out the following year, as there now existed the possibility of confrontation between armed youths of the respective UDF-aligned and Inkatha factions.

According to a major academic study of these events, when the first death in this conflict occurred it appeared to be a case of mistaken identity (Bonnin, 2007). Debby Bonnin’s doctoral thesis describes how Hayco members were attacked by youths associated with Inkatha early in 1987, but states that Sthembiso Mngadi was killed in February after his attackers mistook him for someone else. The assassins had asked about the whereabouts of “a man in a brown hat”, which was an apparent reference to fellow Hayco member Vusi Maduna.

The five killers including a ‘political figure’ from Woody Glen, being driven by a local councillor in a yellow [Ford] Cortina, said they were looking ‘for a man in a brown hat’. They then shot and killed Mngadi who was wearing Maduna’s brown hat at the time.

On that day, as related in Bonnin’s thesis, Sthembiso Mngadi was wearing ‘his friend’s hat’ and was seemingly gunned down in the place of Maduna. This version of events is disputed by surviving friends and family of Sthembiso Mngadi, however. Several interviews conducted by the Local History Museum relate rather that Vusi Maduna was in fact a police informer and secretly a member of Inkatha who gave the brown hat to Mngadi as a marker that the killers used to identifying their target (Gumede interview, 2014; Mvelase interview, 2014; Majola interview, 2014; Matebe interview, 2014).

Furthermore, Maduna is described as ‘Hayco treasurer’ in Bonnin’s thesis but almost 30 years after the events no person from Mpumalanga has any recollection of his holding this office. Instead, he is seen as an agent provocateur who led calls for the organisation to engage in arson and other attacks. In consultations with community members and stakeholders in the process to create the new Mpumalanga Heritage Centre there is widespread disbelief that Maduna is portrayed in an academic text as an office holder and innocent bystander in the death of Sthembiso Mngadi. The opportunity to present alternative versions of this central event in the Mpumalanga violence has formed a central theme in the oral history project conducted over the past two years.

In the week that followed the killing of Sthembiso Mngadi, three more Hayco members died at the hands of other unidentified assassins. The response from their UDF-associated comrades was now seen as unavoidable and Inkatha leaders were attacked at Clermont township near Durban, while the chairman of Inkatha from Woody Glen was killed in the middle of March.

The wider situation then rapidly deteriorated after a school athletics meeting between athletes from Hammarsdale, Wartburg, Camperdown and Inchanga in April 1987 became the scene of open violence (Bonnin, 2007). Athletes and their supporters were questioned aggressively concerning their political allegiance, and any UDF supporters or Azapo members were severely beaten. By this stage political activity had evolved into vicious confrontation, and the youth of Mpumalanga were no longer recognisable to their elders as factions turned upon one another. For the next three years Mpumalanga remained in the grip of violence that characterised the final phase of apartheid in South Africa.

The particular forms of violent clashes that erupted in 1987 and continued with increased force, divided the community into pockets of political loyalties which set entire sections of the township against one another. One of the most distinctive elements of this conflict was the absence of impartiality; literally everyone was forced to take sides regardless of their own privately held opinions. The simple fact of residence in one place or another largely indicated the allegiance held by the people living there, and exposed their families to indiscriminate attack from the opposing side. The division of ‘territory’ was a major element in this conflict (Majola interviews, 2014).

While earlier incidents of factional violence witnessed deaths by stabbing, soon after killings and attacks commenced at Mpumalanga more deaths by gunshot wounds were reported. Weapons were either rifles or handguns acquired through various channels or homemade pistols known as uqhwasha in Zulu. Proliferation of firearms at Mpumalanga was an indication of the deliberate hostility between respective groups at that time. There was also a marked increase in arson as the homes of opponents were set on fire, and the inhabitants fleeing the blazes were subsequently killed as well. Tragically, a sexual dimension of the violence was exhibited in the large numbers of rapes reported during the political violence as well (Bonnin, 2007).

As was the case in other parts of KwaZulu-Natal, Inkatha secretly requested military support in Mpumalanga from government security forces such as SAP and SADF (Luthuli interview, 2014; TRC transcripts, 1998). A covert process to provide Inkatha recruits with armed training was code-named ‘Operation Marion’ and resulted in numbers of so-called Caprivi trainees (named after the site of their training) participating in the violence (Luthuli interview, 2014; TRC transcripts, 1997). Regular detachments of the SAP and SADF in armoured vehicles known as ‘Caspirs’ also provided direct assistance to Inkatha amabutho during assaults on UDF areas of the township (Lyster interview, 2014). The presence and actions of both army and police detachments, supposedly to prevent the worst violence, were largely a cause for fear among those communities opposed to Inkatha and the government.

Even at the height of the killings and torching of homes, people who lived through that war-torn time acknowledged the potency of history to record their ordeals. During consultations with community stakeholders during the building of Mpumalanga Heritage Centre, as well as in preparatory meetings for the oral history project, various individuals voiced the belief that by recording their testimony in partnership with eThekwini Municipality participants were fulfilling an undertaking on behalf of both those who died, as well as for future generations.

During her interviews for this project, Mrs Fakazile Mvelase commented that her final offering to the struggle for freedom in South Africa was the oral history she contributed to the museum. During the period of violence she was a senior UDF leader who became a target of several attacks, at her home as well as during the massacre at emaLangeni Cemetery, and one of her sons was killed in the fighting. She explicitly stated that ‘Now that I have told my story, I can die in peace’ (Mvelase interview, 2014). Central to her view is an appreciation that her account of events will be presented in the new museum for a younger generation to view and interrogate alongside any other sources and narratives that may be included.

Declaring respect for the historical record was reflected across the spectrum of former political foes interviewed at Mpumalanga. A poignant summary of the hardships of war was provided by an erstwhile opponent of Mrs Mvelase when he gave his own version of events. Mr Eugene Mlaba was a member of Inkatha, and his brother Sipho Mlaba was an important commander of the Inkatha amabutho or militia forces. When asked what key fact young South Africans should know about this conflict, Mlaba made the following comment:

When udlame (political violence) began, we on our side believed we were fighting for many important principles, which could not be compromised upon. Over time we justified all that happened with the conviction that the most critical issues were at stake. Gradually, death and war became all that we knew. The important principles and values we originally stood up to defend eventually disappeared, and all that was left was war.

War came to sour everything it touched in our lives, and nothing survived. In the end, things that were supposed to be a joy in life, like a marriage or the birth of a child, could not be celebrated because of the conflict. It simply destroyed all our hopes of happiness.

In that time my aunt and I were hiding in a dark house one night, while homes were burnt along our road. We promised each other that if we survived, we would tell the story of this war one day, so that others may learn as well. (Mlaba interview, 2014)

As in the case of Mrs Mvelase and others, Eugene Mlaba expressed great satisfaction that his narrative concerning the battles fought almost three decades ago would be preserved near the sites of this conflict. ‘Let the young people, and visitors from elsewhere, come hear what happened here from the mouths of those that saw it themselves,’ he added.

The peace process (1991-1993)

Attacks escalated through the last years of the 1980s, and the rate of deaths increased even further when political parties, including the African National Congress and South African Communist Party, were unbanned by President F.W. de Klerk in February 1990. Soon afterwards, South African Defence Force detachments that had sometimes acted as buffers between the warring sections of Mpumalanga were withdrawn – much to the horror of women in the township. This action was seen as a precursor to uncontrolled raids. What followed at the beginning of April 1990 was the last large-scale offensive on the UDF/ANC residential areas, resulting in more than 2 000 refugees fleeing their homes (Jeffery, 1997). Mpumalanga was largely deserted by its inhabitants and became a fully-fledged theatre of war for a number of weeks (Sunday Tribune, 8 April 1990).

In the midst of such awful violence, leaders on both sides of the political divide made a decision to re-establish peace talks that had stalled on various occasions in the past (Majola interview, 2014; Mlaba interview, 2014; Mvelase interview, 2014). Although this was a difficult process, the country as a whole was undergoing profound political change too. This time the peace dialogue achieved results. Inkatha and ANC endorsed a nine-point code of conduct drafted by the South African Council of Churches, and only three deaths were reported during July 1990. Militia units of the KwaZulu Police and Caprivi trainees were withdrawn from Mpumalanga shortly after this and soon the death toll in the township was reduced significantly (Bonnin, 2007).

Towards the end of 1990 it was possible for a joint delegation of ANC and IFP leaders to visit the township, and during a meeting between Nelson Mandela and Mangosuthu Buthelezi it was decided to hold a joint peace rally on 18 May 1991 (Natal Witness, 20 May 1991). Slowly communities in different areas of Mpumalanga returned to life as the so-called ‘no go’ restrictions on the movement of people were lifted, schools were reopened and regular meetings took place between representatives of the two former enemy camps. In 1993 the negotiations were brought to a conclusion when the African Centre for the Constructive Resolution of Disputes (ACCORD) designated the community of Mpumalanga as the first recipient of its newly inaugurated Africa Peace Award (http://www.accord.org.za/apa/past-events/1993).

This final element of the peace process, namely the 1993 Africa Peace Award, also forms a contested piece of oral history for many interview subjects at the Mpumalanga Heritage Centre. The problem raised in this respect is the leading role that has long been ascribed to Meshack Radebe, an ANC politician and ‘peace negotiator’ along with Sipho Mlaba of Inkatha. Radebe was named as the ANC representative in the citation of the Africa Peace Award, but his connection with Mpumalanga was called into questioned during three separate interviews (Majola interview, 2014; Mvelase interview, 2014; Gumede interview, 2014).

Although Radebe belongs to the same organisation as the individuals who were interviewed, oral histories given by these three people offer significant variations from the familiar narrative that has been recorded in other sources. According to accounts related by these interview subjects, Radebe only became involved in the Mpumalanga peace process once the worst fighting had subsided and after numerous peace efforts had already been made. Although it is indisputable that the peace efforts he joined were ultimately successful, certain community members contend that Radebe’s association with the end of conflict is simply coincidental and an accident of timing. All three remain inflexible on this point, that peace was made by the community of Mpumalanga themselves, after terrible suffering and pain, without ‘guidance’ from external leaders of the ANC.

During the interviews which form their oral testimony, Gumede, Majola and Mvelase were at pains to stress their awareness of how their account differs from the widely accepted and published narrative (interviews on 14 July and 17 July 2014 respectively). They would, however, prefer that this contested perspective be included in the Mpumalanga Heritage Centre. Since the time of conflict Deputy Speaker Meshack Radebe has maintained an influential 20-year political career in the region, and currently holds office in the provincial legislature. He was invited to present his account of how the peace of Mpumalanga was achieved, as part of the oral history project, but was unable to participate due to illness on the day of his interview.

Conclusion

The civil war endured by the community of Mpumalanga from 1985 to 1991 remains a vivid memory for those who survived this conflict. More than 20 years since the fighting ended, there is also a resolve among survivors to record their experiences and subjective opinions regarding this terrible period in their lives. Although one of the participants is also writing a personal history of the political violence, the process of documenting oral history is regarded as the most effective way to preserve these personal recollections.

Furthermore, each of the participants who contributed an oral history to the project for Mpumalanga’s Heritage Centre enthusiastically endorsed the use of their statement as part of museum displays within the community. The interviews have been filmed and will be accessible to visitors to consult and compare in the completed heritage centre. While textual and graphic displays provide a summary narrative of what occurred in the violence, and supply statistics, representatives of the community will essentially relate their own contested accounts concerning their perspectives of a variety of incidents, some of which have been presented in this paper. The educational value of these testimonies in Mpumalanga is invaluable to this community